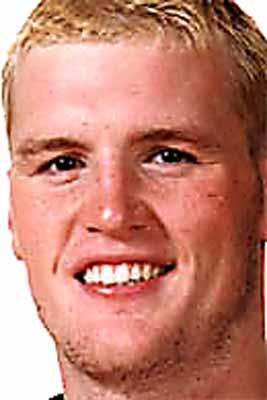

Trevor Ettinger (1980-2003)

Our Thoughts and Prayers go out to Trevor's

Family and friends. Click

HERE to post your thoughts or memories on Trevor.

A webiste Dedicated to Trevor

http://www.trevorettinger.tz4.com/ .

Pictures of Trevor

| |

|

|

Smile forever! |

Trevor giving the Moncton

Wildcat mascot a high five.

Trevor died on July 26th 2003 at

the age of 23. Soar high

Eagle,you will be missed. |

|

|

|

STORIES |

|

|

|

Trevor Ettinger passes

away at age 23

|

By Crunch Staff

|

www.syracusecrunch.com

July 28 2003

Trevor Ettinger,

23, who spent

the past two

seasons with the

American Hockey

League’s

Syracuse Crunch

and East Coast

Hockey League’s

Dayton Bombers,

passed away on

Saturday in

Upper Kennetcook,

Nova Scotia.

Columbus Blue

Jackets

Executive

Vice-President

and Assistant

General Manager

Jim Clark, who

oversees the

hockey

operations for

the Crunch,

Columbus’ AHL

affiliate,

issued the

following

statement: “The

Columbus Blue

Jackets,

Syracuse Crunch

and Dayton

Bombers

organizations

are shocked and

deeply saddened

by the sudden

passing of

Trevor Ettinger.

Trevor was a

tremendous young

man who was very

well liked and

respected by

those around

him. Our

thoughts and

prayers go out

to his family,

friends and

teammates during

this most

difficult time.”

Syracuse Crunch

President and

Chief Executive

Officer, Howard

Dolgon added the

following: “The

passing of

Trevor Ettinger

has touched the

Syracuse Crunch

organization

very deeply. He

was a pleasant

guy who always

had a smile on

his face and

he’ll be missed

on the ice, in

the dressing

room and in the

community. Our

sincerest

condolences go

out to his

family and

friends.”

A memorial

service will be

held on

Wednesday at 2

p.m. (Atlantic)

at the Ettinger

Funeral Home

(2812 Main St.,

Shubenacadie,

Nova Scotia B0N

2H0). The family

has requested

donations be

made to the East

Hants Minor

Hockey

Association (c/o

Hockey Nova

Scotia, Suite

910, 6080 Young

St., Halifax,

Nova Scotia B3K

2A2) or to an

animal shelter

or charity of

choice.

|

|

|

|

|

Former

Cats Captain Dies

|

By Crunch Staff

|

www.syracusecrunch.com

July 28 2003

UPPER KENNETCOOK,

N.S.

Former Moncton

Wildcats

defenceman

Trevor Ettinger

died suddenly

and unexpectedly

on Saturday

afternoon at his

mother’s house

in Upper

Kennetcook, N.S.

He was 23 years

old.

"I spoke with

his mother

(yesterday

morning)," said

Bruce Morrison,

who became a

close friend of

Ettinger when he

played for

Moncton in the

Quebec Major

Junior Hockey

League.

"She wanted me

to pass along

word to the

Wildcats fans

and close

friends that he

made while he

was here. She

came home from

work on Saturday

and found Trevor

deceased in the

house. She was

in a state you

would expect to

find a grieving

mother. She was

in a state of

shock."

RCMP in Upper

Kennetcook

didn’t return

phone calls

yesterday to

discuss details

of Ettinger’s

death. Funeral

arrangements

haven’t yet been

finalized for

the former

Wildcats

captain.

Morrison was a

billet for

former Wildcats

players Mirko

Murovic and

Bobby Reed.

"Trevor was at

my house a lot

hanging out with

those guys,"

said Morrison.

"I have pictures

of them all

together. I

became good

friends with

Trevor. I was

with him in May

at his house in

Kennetcook and

we had a good

conversation.

"He just signed

a new contract

and his career

was on track. He

was in good

spirits. We had

made

arrangements to

go on a

motorcycle ride

together. He was

invited to my

son’s wedding,

but then I

didn’t hear from

him for awhile.

"My wife hasn’t

stopped crying

all day since

hearing the

news. We’re both

very devastated.

You get to know

the players and

they become

family. We

considered

Trevor one of

the family and

we’ve always

stayed in touch

with him after

he left Moncton."

Ettinger split

his four QMJHL

seasons between

Moncton, the

Cape Breton

Screaming Eagles

and Shawinigan

Cataractes. He

had 33 points

and 1,366

penalty minutes

in 251 career

games.

The enforcer

defenceman

6-foot-5 and 230

pounds - spent

the second half

of 1999-2000 and

the first half

of the following

season with the

Wildcats. He was

the league’s top

fighter and his

combination of

physical play

and outstanding

personality made

him one of the

club’s all-time

fan favourites.

"He was a

tremendous part

of our

organization, a

tremendous

leader both on

and off the

ice," said

Wildcats

vice-president

Bob Crossman.

"He was well

respected by the

fans and his

teammates. It’s

just a tragic

loss for sure."

Ettinger was a

sixth-round pick

of the Edmonton

Oilers in the

1998 National

Hockey League

draft, but he

didn’t sign a

contract. He

later hooked on

as a free agent

with the

Columbus Blue

Jackets.

He spent his

first two

professional

seasons in the

East Coast

Hockey League

and American

Hockey League.

In June, he

signed a new

two-year AHL

contract with

the Syracuse

Crunch, the top

farm club for

Columbus.

"We became good

friends with

Trevor and his

mother," said

Morrison. "It’s

hard to take,

especially with

a 23-year-old

kid who had a

good future and

a lot going for

him. You can’t

imagine what his

mother is going

through. Our

thoughts and

prayers are with

her.

"Trevor was

always very

popular. He had

a great

personality.

Everybody liked

him as both a

player and

person."

Columbus general

manager and head

coach Doug

MacLean

commented on

Ettinger’s

death.

"It’s just an

unbelievable

tragedy," he

said. "I really

don’t know any

details. It’s a

tragedy for both

us and his

family. To say

the least, I’m

shocked. We saw

him as a good

solid kid for

Syracuse. We

were pleased

with his

development."

Anton Thun was

Ettinger’s agent

since he was a

16-year-old

playing in the

Nova Scotia

Midget AAA

Hockey League.

"I’m sure

everybody is

grasping at

straws (with

regards to

Ettinger’s

sudden and

unexpected

death)," he

said.

Donnie Miller,

Ettinger’s

uncle, is trying

to come to terms

with news that

the youngster

was found dead

at home.

"He was the

happiest person

there was

around," he

said. "He always

had a big smile

and hug and

handshake for

everyone he met.

People are

devestated,

shocked. There

is no way to

describe it.

Hockey was his

life. It’s all

he ever lived

for."

Ettinger had 11

points and 359

penalty minutes

in 68 career

games for

Moncton. Real

Paiement was

shocked to hear

of the player’s

death.

"He was strong

physically. He

also seemed

strong

mentally," said

Paiement, who

was Ettinger’s

head coach with

the Wildcats in

1999-2000.

"I remember that

he was a great

leader. He was a

smart player who

knew his role.

Before we traded

to get him, I

was told he had

great leadership

qualities and he

demonstrated

that.

"For him, there

was no

difference

depending on

your language,

race, religion

or anything

else. He treated

everyone the

same way. He fit

in very well

with everyone

because of his

personality. He

handled himself

well - always

polite, direct

and honest. He

had a lot of

qualities to

like. He was a

solid young

man."

|

|

|

|

|

Former

Wildcat Ettinger dies,

23 |

By Neil Hodge|

Times and

Transcript |

July 28 2003

The Moncton

Wildcats are

mourning the

loss of one of

the most popular

players in team

history.

Former Wildcats

defenceman and

captain Trevor

Ettinger died

suddenly and

unexpectedly on

Saturday

afternoon at his

mother's house

in Upper

Kennetcook, N.S.

He was 23 years

old.

"I spoke with

his mother

(yesterday

morning)," said

Bruce Morrison,

who became a

close friend of

Ettinger when he

played for

Moncton in the

Quebec Major

Junior Hockey

League.

"She wanted me

to pass along

word to the

Wildcats fans

and close

friends that he

made while he

was here. She

came home from

work on Saturday

and found Trevor

deceased in the

house. She was

in a state you

would expect to

find a grieving

mother. She was

in a state of

shock."

RCMP in Upper

Kennetcook

wouldn't return

phone calls

yesterday to

discuss details

of Ettinger's

death. Funeral

arrangements

haven't yet been

finalized.

Ettinger split

his four QMJHL

seasons between

Moncton, the

Cape Breton

Screaming Eagles

and Shawinigan

Cataractes.

The enforcer

defenceman -

6-foot-5 and 230

pounds - spent

the second half

of 1999-2000 and

the first half

of the following

season with the

Wildcats. He was

the league's top

fighter and his

combination of

physical play

and outstanding

personality made

him one of the

club's all-time

fan favourites.

Ettinger was a

sixth-round pick

of the Edmonton

Oilers in the

1998 National

Hockey League

draft, but he

didn't sign a

contract. He

later hooked on

as a free agent

with the

Columbus Blue

Jackets.

He spent his

first two

professional

seasons in the

East Coast

Hockey League

and American

Hockey League.

In June, he

signed a new

two-year AHL

contract with

the Syracuse

Crunch. That's

the top farm

club for

Columbus.

"Once we know

funeral details,

we'll certainly

be sending

something," said

Wildcats

business manager

Bill Schurman.

"We'll have a

delegation there

representing the

organization.

"It's certainly

a sad day for

his family and

the Wildcats

organization. We

certainly send

our condolences

to his family

and friends. He

gave everything

he had to the

Wildcats and

represented

himself well on

and off the ice.

He was a Wildcat

at heart. We're

proud to call

him an alumni."

|

|

|

|

A

Fight Too Tough

|

By Lindsay

Kramer |The

Post-Standard

| October 4

2003

Play the

game. That's

what

Syracuse

Crunch coach

Gary Agnew

used to tell

Trevor

Ettinger.

Skate a

little. Show

me what

you've got.

But to

Ettinger,

the team's

enforcer,

playing the

game meant

something

else. It

meant a nod,

a glare, a

smile. Some

unspoken

gesture to

stoke the

fire of a

tough guy on

another

team.

If the fire

caught,

gloves would

drop to the

ice. The

combatants

would rip

and tug at

each other's

jerseys,

straining

for an

advantage.

Fists would

fly.

Ettinger

would

sometimes

let his foe

land a few

punches. But

he'd hold

on, and as

his opponent

wore out,

Ettinger

would draw

upon his

6-foot-5,

240-pound

reservoir of

strength and

throw more

punches of

his own.

Torrents of

them.

He'd lean

into his

opponent,

grinding him

to the ice.

Foes would

try in vain

to escape,

but Ettinger

would grab

them, shake

them, pull

them near.

He punched

and punched

and punched.

Sweat flew

off his

bleached

hair.

Sometimes

when he was

close to

finishing

the job he'd

glance at

his bench

with a

check-this-out

grin. Then

he'd hammer

away some

more until

an official

would step

in and end

the battle.

On the way

to the

penalty box

Ettinger

would raise

his hands ¯

ones

sometimes so

gnarled and

sore from

fighting

that he

couldn't

grasp a

hockey stick

¯ and wave

them wildly.

"Let's go!"

he'd yell to

his

teammates.

"Come on!"

As the

hometown

crowd

roared,

Ettinger

would leave

the ice, his

jersey and

pads askew.

Teammates

would tap

their sticks

on the ice

in the

universal

hockey

gesture of

appreciation.

Trevor

Ettinger

fought to

show loyalty

to his

teammates

and earn

approval

from fans,

and he

usually won

on both

counts.

Off the ice,

Ettinger

fought a

different

kind of

fight. He

worried

about life

after

hockey, was

saddened by

the ups and

downs of two

romantic

relationships

and, friends

say, he was

growing

weary of

fighting.

On July 26

at the home

he shared

with his

mother, Edna

Wardrope, in

Nova Scotia,

he killed

himself at

age 23.

Now, as the

Crunch

lockerroom

and the War

Memorial

stir again

with signs

of hockey,

many fans

and players

are asking

themselves

why Ettinger

lost that

particular

fight.

Furious

fists,

gentle heart

Ettinger

grew up in

Upper

Kennetcook,

Nova Scotia,

a farming

and logging

community of

about 1,000

that's so

small that

one can find

it only on

very

detailed

maps. It

sits about

an hour's

drive north

of Halifax.

Upper

Kennetcook

includes

perhaps 100

houses, a

couple of

gas

stations,

some stores

and a few

stops signs.

It has no

true main

street, just

a single

primary road

that cuts

through the

town.

Ettinger

lived on a

long dirt

stretch

called

Miller Road.

Actually,

that's what

everyone

else called

it. The road

wound up a

small hill,

an incline

that

Ettinger

dubbed

"Miller

Mountain."

It's a

wooded

region where

Ettinger

loved to

hunt and

fish.

Like many

young

Canadian

boys,

Ettinger

took to

skating

early on. By

the time he

was 11 or 12

it was

apparent his

size ¯ a

head or two

taller than

anyone else

¯ would

eventually

steer him

into a

tough-guy

role.

Although

hockey has

for several

years tried

to tone down

fighting,

teams still

value

enforcers.

The good

ones protect

their more

skilled

teammates

from cheap

shots by

opponents

while at the

same time

creating a

little havoc

by crashing

around the

corners and

the crease.

It's the

toughest job

in the

sport, and

Ettinger

accepted it.

But even as

a teen he

was a gentle

giant,

fighting an

opponent

during a

game and

then buying

the same kid

a drink or

candy bar

afterward.

Dany Dube

coached a

major junior

team in Cape

Breton, Nova

Scotia, when

Ettinger

made his

debut there

in 1997.

Dube

described

Ettinger as

someone more

anxious to

prove

himself as

an all-round

player than

as only a

fighter.

"He knew it

(fighting)

was part of

the whole

mandate,"

Dube said.

"You get

kids who are

fighters.

They will

fight

everywhere,

the street.

He was not

like that. I

don't think

he was a

rough kid at

all. But he

was mean

when it was

time" to

fight during

a game.

Ettinger was

eventually

selected by

Edmonton in

the sixth

round of the

1998 NHL

draft. In

six seasons

of major

junior and

pro play,

Ettinger

scored seven

goals and

compiled

1,892

penalty

minutes in

362 games.

Last year

was

Ettinger's

first season

as a regular

in Syracuse,

and he

posted 145

penalty

minutes in

just 38

games ¯

averaging

nearly one

fight every

other game.

But the

menacing

intentions

of

Ettinger's

fists

contrasted

to the warm

heart he

displayed.

Wherever he

played ¯

from Cape

Breton to

Dayton,

Ohio, to

Syracuse ¯

he quickly

became a

favorite of

fans and

teammates.

He was the

big lug who

chose to

disarm with

a smile. He

sometimes

wore a

baseball cap

that read

"Life is

Good" and he

wanted to

make others

believe that

even when he

didn't.

Ettinger

liked to

wear hats,

many of them

goofy. He'd

buy caps at

restaurants

¯ Subway, or

Bob Evans

for example

¯ and wear

them to

practice to

give his

teammates a

laugh.

At one

school

appearance

in Dayton,

he slipped

on the tall,

stripped hat

of Dr.

Seuss' "Cat

in the Hat."

The children

gathered

around him

come

storytime

because they

knew that

even though

Ettinger was

a

mountainous

man, at

heart he was

one of them.

Ettinger

loved

karaoke.

Once, during

preseason

camp in

Columbus, he

went to a

sports bar

and belted

out Harry

Chapin's

"Cat's in

the Cradle."

As much as

Ettinger

stood out,

he also took

pains to fit

in.

He'd cook

teammates

meals. He'd

pick up

after

roommates.

He was

always

active in

the

communities

where he

played, and

was one of

the most

requested

players for

Crunch

public

appearances.

"He seemed

like he

enjoyed

life, he was

always

smiling,"

said former

Crunch

winger

Mathieu

Darche. "We

all knew

him, but I

guess there

was a part

of him

nobody

knew."

The

season ends

Syracuse

missed the

playoffs and

the 2002-03

season ended

quietly last

April. To an

outsider

Ettinger

seemed

headed home

for another

carefree

summer, but

his private

torment was

already

brewing. At

least one

person, Lisa

Monkley, had

been in the

middle of it

for months.

In the

summer of

2002,

Ettinger

broke up

with his

long-time

girlfriend,

Jessica

Ryan. On the

rebound, he

met Monkley,

30, who

lives on

Prince

Edward

Island. By

September

2002,

Ettinger had

purchased a

three-quarter-carat,

princess-cut

diamond ring

and

proposed.

Monkley,

taken aback

by the

sudden

proposal,

accepted.

Monkley said

Ettinger got

upset when

people

questioned

the

whirlwind

romance. She

remembered

one time

when he

cried after

someone

suggested he

was too

young to

know how he

truly felt.

"I always

thought that

was kind of

strange that

he would get

so emotional

when people

would say

stuff to

him. I just

figured it

was because

he was such

a sensitive

guy and that

it was

sweet,"

Monkley

said. "Maybe

it was

because he

was so

frustrated

that people

were always

telling him

how he

should be

and what he

should be

feeling."

Ettinger

began the

2002-03

hockey

season with

Dayton of

the East

Coast Hockey

League.

Teammates

were aware

that

Ettinger was

engaged, but

said he

shared few

details

about the

relationship.

"I asked him

a few times

and he said,

'It wasn't

right. I

didn't

really think

it out or

plan.' "

That's the

kind of guy

he was. He

just went

with

things,"

said Dayton

teammate

Chris

Thompson.

Ettinger was

promoted to

Syracuse on

Nov. 29. Two

weeks later,

about 90

minutes

before a

game against

Wilkes-Barre/Scranton,

Ettinger

called

Monkley and

said he had

something to

tell her. He

said he

couldn't

speak at the

time, but

Monkley said

she demanded

to know what

was wrong.

Ettinger

said he

couldn't

marry her.

During the

five-minute

conversation

Monkley ¯

who said she

thought the

relationship

had been

going well ¯

pressed

Ettinger for

reasons, but

he was vague

and

game-time

was

approaching.

Ettinger

talked again

to Monkley

when he went

home for

Christmas.

Monkley said

Ettinger

told her he

still felt a

strong

attachment

to her, but

he was

uneasy about

their

relationship.

Ettinger was

having

trouble

moving on

from both

Ryan and

Monkley.

Monkley said

Ettinger

persisted in

calling her.

She said he

would cry,

but he

couldn't

explain why

he was so

upset.

Slipping

away

In March,

Monkley said

Ettinger

called her

and left a

message that

he was

having

problems.

Ettinger

said he'd

call back

later to

discuss

them. He

never did.

Others also

had trouble

getting

through to

Ettinger.

Thompson,

the former

teammate,

said his

friend

ignored

messages.

When

Thompson did

get through,

Ettinger

would say he

had to run

and would

promise to

call back.

Ettinger

wouldn't.

Monkley saw

Ettinger in

June when

she visited

Truro, Nova

Scotia,

where

Ettinger was

temporarily

living.

Monkley said

Ettinger

again broke

down and

told her he

was

depressed

and

confused.

Ettinger and

Monkley

eventually

hugged

goodbye.

Ettinger

held on for

so long and

so tightly

that Monkley

had to push

herself

away.

At the same

time

Ettinger was

going back

and forth

with Monkley,

he was also

trying to

patch things

up with

Ryan. Ryan

declined to

be

interviewed

for this

story.

Josh Dill,

Ettinger's

close friend

and former

teammate in

junior

hockey, said

Ettinger

carried

guilt about

hurting Ryan

and Monkley.

"He told me

'I screwed

up two

girls'

lives.' He

felt pretty

bad about

everything,"

Dill said.

Ettinger

also worried

about his

career.

Friends said

he fretted

about

whether he

had the

talent to

reach the

NHL and if

his high

school-level

education

would be

enough to

get him a

good job.

Dill, who

spoke to

Ettinger

three days

before the

suicide,

said his

friend

longed for

his earlier

hockey days.

"He didn't

want to grow

up. He was

always

talking

about how

much fun

junior

(hockey)

was, he

didn't have

a lot of

responsibilities,"

Dill said.

"I think

maybe

fighting was

getting to

him. What he

said was how

he's getting

older, he

didn't think

they

(Columbus)

were going

to bring him

up. He

didn't know

what he was

going to do

after

hockey."

Agnew said

Ettinger was

an eager

student who

kept those

worries to

himself.

After last

season,

Ettinger

signed a

one-year

contract

worth

$50,000 to

play with

the Crunch

again this

year.

However, by

late June,

Ettinger's

dedication

to hockey

was fading.

Larry

Wallace,

Ettinger's

personal

trainer,

said

Ettinger's

workouts

dipped from

about five

times a week

to two or

three.

Wallace said

Ettinger was

caught in

the quandary

of worrying

whether he

would be in

shape for

the upcoming

season and

then

becoming so

depressed

that he'd

skip

training

sessions.

Wallace said

Ettinger

grew quiet

and

preoccupied.

He rarely

smiled.

"It was the

darker side

we started

to see,"

Wallace

said. "To

explain it,

as far as

his

depression,

he couldn't

explain it

himself.

He'd

basically

shrug it

off. I'd pry

more and

more, but I

got the

impression

these are

things he

had to work

out. He

didn't seem

to have the

ability in

the last few

days to

(know) how

to cope."

Ettinger

withdrew

from

everyone.

"He was so

worried

about what

everyone

else

thought. He

wanted to

make

everyone

else happy.

He just

wasn't

taking care

of himself,"

Monkley

said. "I

just think

with him

trying to

make

everyone

else happy,

he lost part

of himself

along the

way."

Wayne

Martin, who,

along with

his wife,

Jean, let

Ettinger

live with

them during

his career

in Cape

Breton, said

the dam

holding back

Ettinger's

feelings of

guilt over

his broken

engagement

and what he

viewed as a

stalled

career might

have cracked

once he lost

hockey as a

distraction.

"As long as

he was at

the rink and

playing with

the boys,

his life was

full. As

soon as he

hit home,

the fast

pace

stopped. It

hit him

then," Wayne

said. "He

has such a

high profile

in that

area. Seeing

all his

friends

probably

caused him

pain."

Dill, who

used to hang

out with

Ettinger

during

summers,

said he

didn't see

Ettinger at

all last

summer and

had trouble

reaching him

on the

phone.

"He didn't

want to do

anything. He

just wanted

to be by

himself. He

said he was

depressed,

he wasn't

happy with

life," Dill

said.

Wardrope,

whom others

described as

having a

very close

relationship

with her

son, also

was shut

out.

"He just

didn't seem

quite

himself when

he came

home. He

just didn't

seem as

gung-ho as

usual," she

said.

"Usually

with me he'd

tell me not

to worry,

everything

was fine."

'A little

boy who was

sick'

he Martins

said when

Ettinger

lived with

them he was

always the

first to get

up and greet

strangers at

the door.

They said

their phone

was

constantly

ringing with

calls from

his friends

wanting to

go out with

him.

The Martins

saw a much

different

Ettinger

when they

visited him

for the

weekend

before his

death. They

thought

they'd be

prepared

because

Wardrope had

cautioned

them about

the change

in her son's

appearance

and

demeanor.

Still, they

were

shocked.

Ettinger,

whom Jean

Martin said

showered

three or

four times a

day when he

lived with

her, was

unkempt and

sported

stubble on

his face and

long hair.

Normally

very

organized,

Ettinger

still hadn't

unpacked his

boxes from

Syracuse.

Ettinger was

wasting

away. Wayne

Martin

looked at

him and

wondered

where his

once-wide

shoulders

went.

Ettinger had

lost about

30 pounds

and he had a

desperate

look.

"When we saw

him it was

like he was

10 years

old, the way

he'd look at

his mother,

like a

little boy

who was

sick," Jean

said.

At one meal

during their

visit,

Ettinger

excused

himself from

the table

and took

refuge by

lingering in

the

bathroom.

Ettinger's

role as an

enforcer

demanded

that he lay

himself bare

in front of

a crowd

every game.

Every punch

absorbed,

every facial

gash ripped

open, every

knockdown to

the ice was

a weakness

for

thousands to

see.

Now, the man

who accepted

such

potential

humiliation

nightly

withered

under the

gaze of his

closest

friends.

"He had a

big smile on

his face,

but you knew

he was

forcing it,"

Wayne Martin

said. "He

just

couldn't be

around

people. When

he'd go into

a room or

into a

restaurant,

he'd want to

leave. He

thought

people were

looking at

him. He knew

he was a lot

smaller than

usual. He

said 'I'm

just having

trouble

being in

rooms with

people.' "

Perhaps more

to please

others than

himself,

Ettinger

took baby

steps toward

help. Dill

said

Ettinger got

medicine to

counter the

depression

and had an

appointment

with a

doctor on

Friday, July

25, the day

before his

death.

But Dill

said

Wardrope

told him

that

Ettinger

didn't take

the medicine

and he

skipped the

appointment.

"I think he

was wanting

to go to the

doctor. But

he couldn't

bring

himself to

go. Ten feet

tall and

bulletproof,

that's what

he thought

he should

be," Wayne

Martin said.

As Martin

left

Ettinger's

house on the

Sunday

before his

death, the

two chatted

on the way

to the

Martins'

vehicle.

"How do I

look?"

Ettinger

asked.

"You don't

look good,"

Martin

replied.

"You look

underweight.

You may not

want to try

going to the

States and

playing at

that weight

and size."

"I'm going

to see the

doctor on

Friday,"

Ettinger

said, "and

I'll do what

he says."

Martin said

he sensed

Ettinger was

just telling

him what he

wanted to

hear. Martin

made a

mental note

to call

Ettinger on

Saturday to

see how the

appointment

went.

Jean dialed

the phone

Saturday

evening. The

news was

bad.

In his

bedroom just

hours

before,

Ettinger had

lost the

biggest

fight of

all, the

private one

in his head,

when he put

a

.22-caliber

rifle to his

right cheek

and pulled

the trigger.

More than

800 signed a

guest book

at a

memorial

service for

Ettinger

July 30 in

nearby

Shubenacadie.

Wardrope

said she

received

sympathy

cards,

flowers and

emails from

Ettinger's

fans in

Syracuse.

"I honest to

God believe

he was

sick,"

Wardrope

said. "He

just hid it

very well."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trevor's

Stats |

|

Team |

League |

Season |

GP |

G |

A |

PTS |

PIM |

|

Cape Breton |

QMJHL |

1997-98 |

50 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

181 |

|

Cape Breton |

QMJHL |

1998-99 |

61 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

376 |

|

Cape Breton |

QMJHL |

1999-00 |

44 |

1 |

8 |

9 |

328 |

|

Moncton |

QMJHL |

1999-00 |

24 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

153 |

|

Moncton |

QMJHL |

2000-01 |

44 |

3 |

5 |

8 |

206 |

|

Shawinigan |

QMJHL |

2000-01 |

28 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

122 |

|

QMJHL Totals |

|

4 |

251 |

6 |

28 |

34 |

1366 |

|

Dayton |

ECHL |

2001-02 |

48 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

209 |

|

Syracuse |

AHL |

2001-02 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

46 |

|

Dayton |

ECHL |

2002-03 |

18 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

126 |

|

Syracuse |

AHL |

2002-03 |

38 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

145 |

|

ECHL Totals |

|

2 |

66 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

335 |

|

AHL Totals |

|

2 |

45 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

191 |

|

|

Special Thanks to halifaxherd.ca

|